Maxfield Sparrow

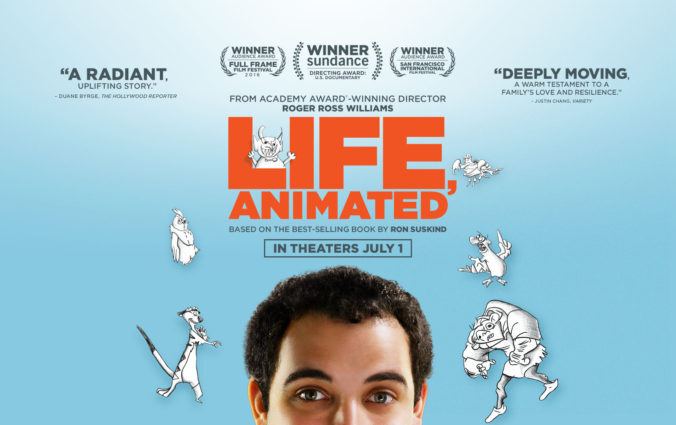

Last week I went with friends to the Portland Museum of Art in Portland, Maine, to see the indie documentary, Life, Animated.

Life, Animated is based on a book by Ron Suskind, a journalist and father to Owen Suskind, the Autistic young man who is the film’s subject and an absolute delight. Owen’s greatest love in life is Disney movies and these films have sustained him through many dark years of isolation and bullying (years Owen calls “glop”) as well as all the disappointments and tragedies a well-lived life can bring. And Owen’s life is well-lived, indeed. He is a charming man, a natural leader, and a deep thinker.

I write this review as an Autistic adult, myself, and I found much in this movie that made me rejoice. I confess that I was troubled by some of the language used, for example when Owen’s father talks about feeling as if someone had kidnapped his child, then later discovers Owen was “still in there” and sets himself about a “rescue mission” to “pull him out” of the “prison of autism.” I was torn at those points in the movie, between an empathy for Owen’s family, feeling themselves at a loss to communicate effectively with their child and a heavy feeling in my heart at hearing an Autistic person described that way.

But I came away from the movie realizing that Owen, himself, had similar feelings about his relationship to the world. While he never directly said, “being an Autistic child was like living in a prison,” he talks about feeling so overwhelmed by all the sounds around him that fought for his attention and made people’s voices “a garble.” And when Owen talks about his glop years, he is clearly distressed by how badly he was bullied and how lonely he felt.

Ron tells a story of connecting with Owen through a hand-puppet of Iago, the parrot from the Disney animated film Aladdin. When Ron spoke to Owen through Iago, Owen said that he was sad because he had no friends. I realized that, as much as I hate the phrase “prison of autism” and how it puts all the blame for communication barriers on the Autistic person and implies that we are the ones who must do all the work to enter someone else’s world, Owen’s experience of growing up Autistic must have felt very much like being imprisoned in glop.

I also came to terms with Ron’s use of language because he didn’t simply decide that Owen was “locked away” and had to come join “the real world,” but, together with his wife, Cornelia, and Owen’s older brother, Walter, he entered Owen’s world. When the family realized that Owen was using Disney movies to communicate, the whole family used Owen’s love of Disney as an entry portal to join him in his world. That was what made this movie so beautiful to me: that the family encouraged Owen’s deep love for Disney and found their way into his world. Suddenly autism isn’t as much of a “prison” when the whole family has opened that door with love and performed their “rescue” by entering and joining Owen.

I recommend this movie to anyone with a compassionate heart. Owen will charm you. His life progress will cheer you. The way Owen feels his pain deeply will move you. Owen’s ability to process his pain and move through it to the happiness beyond will impress you. Owen is a man with a powerful vision of justice, loyalty, and independence.

While his father produced it, this is Owen’s film in every aspect. Owen’s parents and brother worry about what will happen to Owen when his parents have aged and passed away, but Owen will be just fine and we, the viewers, see that when Owen pauses The Lion King to ask the Disney club he formed at his school, “what was Mustafa teaching Simba?” Members of the club offer insightful responses and Owen agrees, summing up their words by saying, “when our parents can no longer help us, we have to figure out things on our own.”

Owen is figuring things out. He is moving forward into the world, “a little bit nervous and a little bit excited,” and discovering that he can succeed as an adult without losing the magic and wonder of childhood. He has memorized every Disney film and he has internalized the valuable lessons they teach about friendship, courage, and honor.

His parents still get teary-eyed when they talk about the early days when Owen was first diagnosed with autism. But only moments later, they are clearly bursting with pride at what a lovely, strong man Owen has grown to be. Owen is, in his own words, “a proud Autistic man.” The viewer will leave the theater feeling proud of Owen, too. I found his journey through the darkness of glop and back into the light, with the help of the timeless Disney stories, inspirational for my own journey through the glop of anxiety and depression, loneliness and bullying, isolation and deprivation. Owen has saved his own life with stories and, in the process, become a storyteller in his own right.

Owen’s prison was not autism. He is still Autistic and he will always be Autistic. Owen’s prison was isolation from others. What saved Owen’s life was not being pulled out of autism, as if that were even possible. (It’s not. Autism is how his brain is wired and as deep a part of who he is as the Disney stories he loves so much.) What saved Owen was communication. When Owen’s family learned how to communicate with him, they opened a path of connection that grew stronger every day.

For me, the strongest messages Life, Animated brings to parents of Autistic children is to never give up on finding a way to communicate with your child and never give up on helping your child find a way to communicate with the world.

At one point, Owen communicated by repeating a line from The Little Mermaid over and over: “just your voice. Just your voice.” Owen’s pediatrician said it was merely echolalia, signifying nothing. Ron seemed to agree with the assessment on the surface, but beneath that agreement, he clearly harbored a secret hope that it did signify something. In my opinion, Ron was right. Echolalia is communication, as many parents of Autistic children who speak in quotes will quickly tell you. Many Autistic adults who were echolalic when younger (or still are as adults) but have developed a more independent voice will agree: when they were, or are, echolalic, communication is still happening on their part, even when it’s not getting picked up and understood by the recipient.

Ron did not so quickly dismiss the echolalia as meaningless. Moreover, at one point in the film, Ron extends the question of meaning, asking, “who decides what a meaningful life is?” Ron never directly answers that question, but he doesn’t have to. Owen has a meaningful life by anyone’s measure.

But the only measure that really matters in the end is Owen’s. Owen said he didn’t feel like a hero; he felt like a sidekick. But in re-making the Disney canon into a story that was truly his, he rose to become a hero among sidekicks and the protector of them all. Owen has crafted a meaningful life on his terms.

Life, Animated is a celebration of communication, of victory, and of an Autistic life well-lived. I hope you have a chance to see it soon yourself. The film offers much to think about and discuss as our culture struggles to understand what autism is and how Autistics can be welcomed and honored as full participants in society. We can be helped to find our own way in the world as narrators of our own life stories.

—-

This post was previously published at unstrangemind.com.