Emily Willingham

You’ve probably seen a lot of headlines lately about autism and various behaviors, ways of being, or “toxins” that, the headlines tell you, are “linked” to it. Maybe you’re considering having a child and are mentally tallying up the various risk factors you have as a parent. Perhaps you have a child with autism and are now looking back, loaded with guilt that you ate high-fructose corn syrup or were overweight or too old or too near a freeway or not something enough that led to your child’s autism. Maybe you’re an autistic adult who’s getting a little tired of reading in these stories about how you don’t exist or how using these “risk factors” might help the world reduce the number of people who are like you.

Here’s the bottom line: No one knows precisely what causes the extremely diverse developmental difference we call autism. Research from around the world suggests a strong genetic component[PDF]. What headlines in the United States call an “epidemic” is, in all likelihood, largely attributable to expanded diagnostic inclusion, better identification, and, ironically, greater awareness of autism. In countries that have been able to assess overall population prevalence, such as the UK, rates seem to have held steady at about 1% for decades, which is about the current levels now identified among 8-year-olds in the United States.

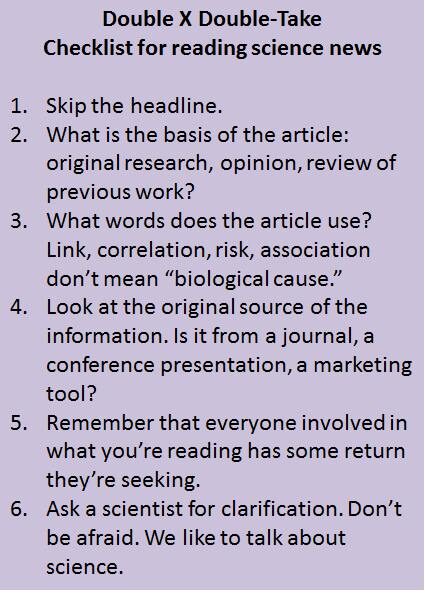

What anyone needs when it comes to headlines honking about a “link” to a specific condition is a mental checklist of what the article — and whatever research underlies it — is really saying. Previously, Double X Science brought you Real vs Fake Science: How to tell them apart. Now we bring you our Double X Double-Take checklist. Use it when you read any story about scientific research and human health, medicine, biology, or genetics.

The Double X Double-Take: What to do when reading science in the news

1. Skip the headline. Headlines are often misleading, at best, and can be wildly inaccurate. Forget about the headline. Pretend you never even saw the headline.

2. What is the basis of the article? Science news originates from several places. Often it’s a scientific paper. These papers come in several varieties. The ones that report a real study — lots of people or mice or flies, lots of data, lots of analysis, a hypothesis tested, statistics done — is considered “original research.” Those papers are the only ones that are genuinely original scientific studies. Words to watch for — terms that suggest no original research at all — are “review,” “editorial,” “perspective,” “commentary,” “case study” (these typically involve one or only a handful of cases, so no statistical analysis), and “meta-analysis.” None of these represents original findings from a scientific study. All but the last two are opinion. Also watch for “scientific meeting” and “conference.” That means that this information was presented without peer review at a scientific meeting. It hasn’t been vetted in any way.

3. Look at the words in the article. If what you’re reading contains words like “link,” “association,” “correlation,” or “risk,” then what the article is describing is a mathematical association between one thing (e.g., autism) and another (e.g., eating ice cream). It is likely not describing a biological connection between the two. In fact, popular articles seem to very rarely even cover scientific research that homes in on the biological connections. Why? Because these findings usually come in little bits and pieces that over time — often quite a bit of time — build into a larger picture showing a biological pathway by which Variable 1 leads to Outcome A. That’s not generally a process that’s particularly newsworthy, and the pathways can be both too specific and extremely confusing.

4. Look at the original source of the information. Google is your friend. Is the original source a scientific journal? At the very least, especially for original research, the abstract will be freely available. A news story based on a journal paper should provide a link to that abstract, but many, many news outlets do not do this — a huge disservice to the interested, engaged reader. At any rate, the article probably includes the name of a paper author and the journal of publication, and a quick Google search on both terms along with the subject (e.g., autism) will often find you the paper. If all you find is a news release about the paper — at outlets like ScienceDaily or PhysOrg — you are reading marketing materials. Period. And if there is no mention of publication in a journal, be very, very cautious in your interpretation of what’s being reported.

5. Remember that every single person involved in what you’re reading has a dog in the hunt. The news outlet wants clicks. For that reason, the reporter needs clicks. The researchers probably want attention to their research. The institutions where the researchers do their research want attention, prestige, and money. A Website may be trying to scare you into buying what they’re selling. Some people are not above using “sexy” science topics to achieve all of the above. Caveat lector.

6. Ask a scientist. Twitter abounds with scientists and sciencey types who may be able to evaluate an article for you. I receive daily requests via email, Facebook, and Twitter for exactly that assistance, and I’m glad to provide it. Seriously, ask a scientist. You’ll find it hard to get us to shut up. We do science because we really, really like it. It sure ain’t for the money. Edited to add: But see also an important caveat and an important suggestion from Maggie Koerth-Baker over at Boing Boing.

—————————————————————————–

Case Study

Lately, everyone seems to be using “autism” as a way to draw eyeballs to their work. Below, I’m giving my own case study of exactly that phenomenon as an example of how to apply this checklist.

1. Headline: “Ten chemicals most likely to cause autism and learning disabilities” and “Could autism be caused by one of these 10 chemicals?” Double X Double-Take 1: Skip the headline. Check. Especially advisable as there is not one iota of information about “cause” involved here.

2. What is the basis of the article Editorial. Conference. In other words, those 10 chemicals aren’t something researchers identified in careful studies as having a link to autism but instead are a list of suspects the editorial writers derived, a list that they’d developed two years ago at the mentioned conference.

3. Look at the words in the articles. Suspected. Suggesting a link. In other words, what you’re reading below those headlines does not involve studies linking anything to autism. Instead, it’s based on an editorial listing 10 compounds [PDF] that the editorial authors suspect might have something to do with autism (NB: Both linked stories completely gloss over the fact that most experts attribute the rise in autism diagnoses to changing and expanded diagnostic criteria, a shift in diagnosis from other categories to autism, and greater recognition and awareness–i.e., not to genetic changes or environmental factors. The editorial does the same). The authors do not provide citations for studies that link each chemical cited to autism itself, and the editorial itself is not focused on autism, per se, but on “neurodevelopmental” derailments in general.

4. Look at the original source of information. The source of the articles is an editorial, as noted. But one of these articles also provides a link to an actual research paper. The paper doesn’t even address any of the “top 10” chemicals listed but instead is about cigarette smoking. News stories about this study describe it as linking smoking during pregnancy and autism. Yet the study abstract states that they did not identify a link, saying “We found a null association between maternal smoking and pregnancy in ASDs and the possibility of an association with a higher-functioning ASD subgroup was suggested.” In other words: No link between smoking and autism. But the headlines and how the articles are written would lead you to believe otherwise.

5. Remember that every single person involved has a dog in this hunt. Read with a critical eye. Ask yourself, what are people saying vs what real support exists for their assertions? Who stands to gain and in what way from having this information publicized? Think about the current culture — does the article or the research drag in “hot” topics (autism, obesity, fats, high-fructose corn syrup, “toxins,” Kim Kardashian) without any real basis for doing so?

6. Ask a scientist. Why, yes, I am a scientist, so I’ll respond. My field of research for 10 years happens to have been endocrine-disrupting compounds. I’ve seen literally one drop of a compound dissolved in a trillion drops of solvent shift development of a turtle from male to female. I’ve seen the negative embryonic effects of pesticides and an over-the-counter antihistamine on penile development in mice. I know well the literature that runs to the thousands of pages indicating that we’ve got a lot of chemicals around us and in us that can have profound influences during sensitive periods of development, depending on timing, dose, species, and what other compounds may be involved. Endocrine disruptors or “toxins” are a complex group with complex interactions and effects and can’t be treated as a monolith any more than autism should be.

What I also know is that synthetic endocrine-disruptors have been around for more than a century and that natural ones for far, far longer. Do I think that the “top 10” chemicals require closer investigation and regulation? Yes. But not because I think they’re causative in some autism “epidemic.” We’ve got sufficiently compelling evidence of their harm already without trying to use “autism” as a marketing tool to draw attention to them. Just as a couple of examples: If coal-burning pollution (i.e., mercury) were causative in autism, I’d expect some evidence of high rates in, say, Victorian London, where the average household burned 11 tons of coal a year. If modern lead exposures were causative, I’d be expecting records from notoriously lead-burdened ancient Rome containing descriptions of the autism epidemic that surely took it over.

Bottom line: We’ve got plenty of reasons for concern about the developmental effects of the compounds on this list. But we’ve got very limited reasons to make autism a focal point for testing them. Using the Double X Double-Take checklist helps demonstrate that.

—-

Emily’s sage advice was previously published at Double X Science, and featured on Boing Boing.