Lindsey Nebeker is one of our community’s most visible activists, speaking out on topics ranging from autism and dating in Glamour magazine, to the need for more safety and support measures for individuals with autism at a recent Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee meeting. Lindsey was diagnosed with autism at the age of two, and began to speak around age four. She grew up in Tokyo, Japan with her younger brother James, who shares the same diagnosis but faces more challenges. She recently spoke with TPGA about her experience growing up as one of two siblings with autism.

Tell us a little bit about yourself. How old are you, where do you invest your greatest energies, and when did you first receive your autism diagnosis?

I am a pianist/songwriter, photographer, public speaker, and advocate currently residing in the Washington, DC metro area. As a woman in my late twenties, I have experienced a lot of opportunities and challenges in my life’s path. The inner core of my passions reside in music and art, which I use to express an accurate interpretation of my identity — through my piano, my music compositions, and my photographic works. Also, in recent years, I have also invested my energies in contributing to the disability community.

I was born in Tokyo, Japan to a foreign banking executive father and a former English teacher mother. When I was between 12-18 months old, my parents discovered that not everything was “falling in place” for me at the typical rate of a young child. For one thing, I wasn’t talking. Another big thing my parents noticed was that I was unresponsive when they would try to call my name or interact with me. At first they suspected I might be deaf. They took me to a doctor to get my hearing tested and the results indicated that I did not have hearing issues.

Not long afterward, my mother ran across the 1983 magazine article So Near and Yet So Far: Living With Autism, and this was when she had an “a-ha moment” (as Oprah would call it).

In the early 1980s, evaluation services were scarce in Japan. My parents had to wait until their scheduled home leave to the United States to get me evaluated. (A home leave is a period of approved absence for employees living and working in a foreign country to re-visit their home country). By that time, I was two and a half years old.

I was first taken to a child psychologist for an evaluation. Although she was not an autism specialist, she did confirm that I was displaying many of the classic symptoms of autism. However, the psychologist (who once studied under Bruno Bettelheim) did not satisfy all my parents’ concerns as she went on to suggest the Refrigerator Mother theory. My mom did not buy that.

Fortunately, a friend referred my family to a well-respected autism specialist at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). That was where I received an official diagnosis of autism, and eventually where my brother was taken to receive his own autism diagnosis.

My interest in advocacy and public speaking is somewhat based on my own experiences growing up with autism, but it’s more in behalf of my brother, James, and others who like him who have a greater need to be ensured their safety and their rights — concepts that many of us who can speak up for ourselves take for granted.

What is the age difference between yourself and your brother James? Was he diagnosed with autism at an earlier or younger age than you were?

James and I are a little over two years apart. James was also born in Tokyo, and he also received his evaluation at UCLA.

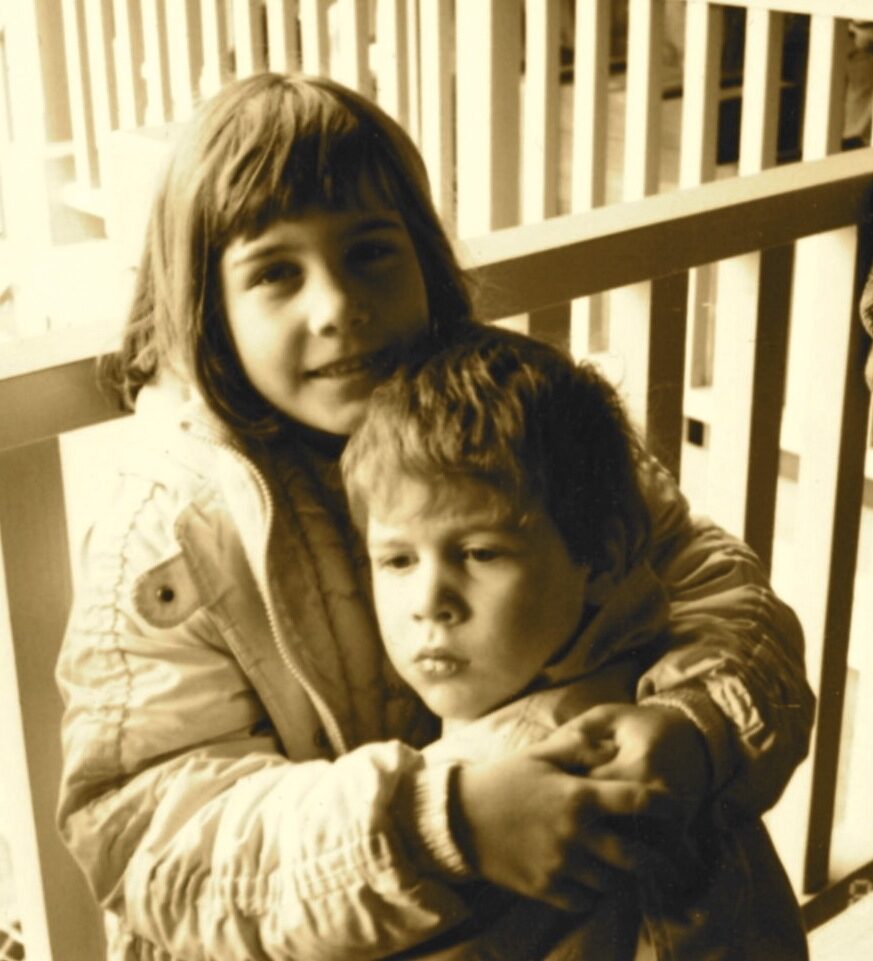

|

| Lindsey and James |

James was, not surprisingly, diagnosed at an earlier age than I was. Because my parents had already experienced the process of picking up on early signs and the diagnosis process with me, they were able to pick up signs from my brother more quickly. Ironically, there was a brief period where he was more responsive and trying to engage with me, while I was the unresponsive one. My parents were actually more concerned about me than they were about James.

The child psychologist (the Bettelheim student) who had made the initial suggestion that I was displaying the classic signs of autism directed my parents’ attention to James (who was less than a year old at the time) and said, “See how you son is different? He appears engaged … he is definitely normal.”

Within two to three years, James and I had “switched places.” As I began to learn how to speak, I was the one trying to engage with James, yet he appeared no longer interested.

What kind of relationship do you and James have, and how has it changed over time?

I have to admit that I wasn’t sure how to answer this, so I sought both of my parents (now divorced) for their wisdom. Both gave very similar responses: “You really didn’t have a relationship with your brother when you both were growing up. Both of you were absorbed in your own activities, played with different things, and had different social lives. You were both living in your own worlds.” Deep down inside, I was always aware of this … but hearing it out loud to me sent chills down my spine.

James and I did walk on different life paths. We began in the same intervention programs and attended the same special education classes. But by kindergarten, that all changed when I transitioned to mainstream schooling. I went to regular grade school, earned a high school diploma, and went on to earn a B.A. degree. James remained in special education programs until he reached the maximum age to attend (age 22), followed by various sheltered workshops and adult day programs. I never thought that was fair, but at the time, my family didn’t know of a lot of resources and supports which accommodated inclusive activities for people with severe developmental disabilities.

I tried very hard to connect with my brother, and I am sure he tried very hard to connect with me, but we never seemed to “cross path.” My brother has always been a mystery to me. It’s odd to admit this considering we share the same diagnosis. To an extent, I understand what he is going through, but it only carries so far.

There were moments when my brother and I would share a laugh, a smile, a hug. They often were prompted, but they were there. Those cherished moments remain in my heart.

Do you know — or know of — many other sibling pairs like yourselves, with two people on very different parts of the spectrum?

I have known of and personally met sibling pairs who have ASD diagnoses. Some of these sibling pairs were twins. I also know of at least two families with five children who are all on the spectrum. Most of these sibling groups do lie on different parts of the spectrum, but not to the degree that James and I do. We are recognizably different at first glance. However, I am sure we are not the only sibling pair who is that way.

Do you think there is a genetic component to autism?

Personal experience can often affect a person in their thoughts and views, and it’s no different with me. Because of my family, and because of a number of other families we know, I feel very strongly that genetics play a role. Whether it is solely genetics or interacted with another factor I have no idea. It’s a very “touchy” subject, and I am cautious from making any claims that I know for certain.

How did your parents support your relationship with your brother, and his relationship with other people?

Throughout the years, James has always been surrounded by excellent support. He had excellent therapists, teachers, and sitters who loved and admired him. However, he had no friends.

Some thought he may not have cared about that, since he didn’t appear to care. Personally, I have never been able to tell what his innermost desires or feelings were. It’s odd to say that because I have autism myself. It attests to how autism is an extremely vast spectrum.

My parents were never able to tell whether their son really loved them or looked up to them as parents. In most cases, he would only come up to us when he wanted something (reaching for a jar of peanut butter, taking off an article of clothing, or a ride to McDonald’s) and had to depend on them to complete the task. After we gave him what he wanted, he would simply grab it and walk off.

Because of the lack of unprompted recognition, it was very difficult to sense he loved or appreciated my parents, and it was even more difficult to feel like he loved or appreciated me… since I couldn’t do as much for him as my parents could. We like to think that he felt that way, but perhaps has no idea how to communicate it to a level the rest of the world understands.

This was where my parents taught me one of the important lessons in life: the art of unconditional love. This means unconditionally loving someone without expecting that communicable love in return.

Unprompted recognition from James was rare, but treasured nonetheless. On a random occasion, he may come up to you, look at you in the eye for a few seconds, smile, and then walk away. We like to think those were moments when he perhaps was expressing his love and appreciation for us.

Have you been involved in your parents’ planning for your brother’s future needs?

Definitely. I always knew that I would have some kind of significant role as a sibling of a person with severe challenges. That role has shaped into different forms as I’ve matured. Initially, my primary role was to take care of James when my mom or my dad had to go on an errand or attend an event. As we approached our teens, and it became more likely that James was going to always need co-dependent living arrangements, I began to accept the possibility of having James come live with me after he exceeded the age limit to attend school. However, my parents got my brother on a waiting list for government funding to cover his housing options. A few years later, at the age of 16, James was granted that funding. At that point, my role changed to James’ potential legal guardian (my parents are currently his legal guardians). I receive copies of his monthly reports that are being sent to my parents so I am kept aware of what is going on.

Even though the state James resides in is responsible for his care, my parents remain his legal guardians until they die, at which point I will become his legal guardian. As a legal guardian, I will have the authority to assist James in making decisions that will be best for him and ensure that he will live a full, productive life. I will have no out-of-pocket expenses for his care as long as the government continues his funding, but if for some reason his funding gets cut or his group home shuts down, I will have to find other residential placement. If I don’t succeed in finding living arrangements that work well for him, I will open up to the possibility of being his sole caretaker, and holding financial responsibility of both our living expenses if he does not receive the accommodations and supports to gain employment.

Currently, I am working out arrangements to acquire communication devices for James to try out again (years ago we tested AAC devices for him without success), and seek the funding required to hire one-on-one assistance to work with him.

What is one thing that being James’s sister has taught you, one thing you’d like other people to know?

I am continuing to learn an invaluable lesson in the humanistic nature of caring for one another. It’s a part of human nature that many of us forget (even myself). As an autistic individual, I have developed a tendency to be self-centered, and to feel like the world has to revolve around me. James keeps me from falling too deep into my self-centered “trance.”

Growing up with the profound differences between my brother and myself in characteristics, strengths and challenges also has allowed me to be open-minded to the differences of the communities, cultures and belief systems that make up our world. This includes the difference in opinions expressed by the ASD community. It does not mean I agree with everything, and (like every person) I have my own beliefs and personal opinions, but I try and listen to all sides of the story.

I have also learned to practice the art of mindfulness. Through my first four years of being nonverbal, I have developed full conviction that those who do not speak understand more than we may realize. I am extremely mindful of speaking to a person rather than at a person. I get highly uncomfortable in the presence of gossip, and whenever I do speak about a person I try my best to practice respect — even when addressing a concern or criticism. If James appears to be completely disengaged while we’re in the same room, I always talk with people as if he is fully present in the conversation. When we sit together in a circle to talk about a person, even if that person doesn’t appear engaged and doesn’t sit with us, let us be mindful and speak as if that person is sitting in our circle, fully present and participating.

I can say things like “James has taught me patience, unconditional love, yada yada.” But it was my parents and my teachers who taught me those principles. I do not see my brother as a teaching tool; I see him as a person who was learning alongside me, at our own individual pace. I cannot deny that our relationship was different from most sibling relationships, and I cannot deny it was a difficult relationship, and I cannot deny that I wished we had a more connected relationship. However, I have no idea what it is like to not grow up with someone like James … it is the only sibling experience I know. So, I choose not to stress on comparing our relationship to the brother-sister relationship that could have been. I love him regardless.

How do you feel about having a loved one in a residential placement? Was it a difficult decision for your parents?

I have a copy of an old family home video with scenes from my brother’s first Birthday party, which I rarely pull out and watch. Recently, I re-watched it, and I remembered why I don’t watch it often. From beginning to end, I wept incessantly. Seeing the moving images of a precious, fiery, red-haired, twinkling eyed little boy full of laughs and smiles. “I’m so sorry, James, that we had to give you up … I’m so sorry that we have caused our family to fall apart … I’m so sorry that I have not been able to be there for you.”

When a member of your family leaves your home to a residential placement, there is an indefinite period of guilt that the family members go through, particularly the parents. I periodically have heart-to-heart conversations with both my mom and my dad about the feelings of guilt that go behind that. “Believe me, it was extremely difficult,” my dad said, “Sometimes I feel like I have abandoned my own son, and it’s excruciating.”

As a parent, you don’t want to feel like you are abandoning your child, and as a sibling, you don’t want to feel like you are abandoning your brother or sister. I admit, it is hard.

Some of my friends are not even aware I have a brother, since James and I are hardly together and he doesn’t live at home. Very few have met him. During my childhood and teen years, I had very few people who wanted to come over to our house. Every time a friend would come over, I had to explain to him or her why James didn’t talk, why he displayed different behaviors, the possibility of him attacking us during his meltdowns, and the possibility of him suddenly appearing without his clothes on (all which has happened).

My parents never desired to send him away, and they tried as long as they could to keep him at home. As helpful as intervention was in developing his basic life skills, he has had a long history of violent behavior during his meltdowns. When he was a little boy, that wasn’t as difficult to handle. Once he became a teenager and developed more strength, the outbursts became increasingly dangerous. It was difficult to predict when they would occur. We often wouldn’t know when he was frustrated or upset until he’d start punching a hold through the wall, ramming his head through a window, or attacking anyone that was around him. Not only was he injuring other people, he was injuring himself — and that was an extreme concern.

Whenever we were in the car, it’d get especially frightening. If we sensed James was going to attack the person who was driving (a parent or myself), the remaining passengers would have to make sure he didn’t grab hold of the driver and lose control of the wheel.

This was not easy for me to accept when I was growing up with James. I often felt injustice whenever he would hurt or attack me when I had done nothing to him.

My mother was probably the most affected by all this. I remember as a high school student being asked to take photos of her bruises, black eyes, and bite marks so she could send them to the state to plead they bump him up the waiting list and provide funding for the services he desperately needed. At one point, my mother was on the verge of picking up the phone and dialing 911.

There is nobody to blame for this. I completely understood why James would handle his emotions this way. As a person who has never been able to speak, has not succeeded in utilizing an AAC device, and knows a maximum of 10 sign language symbols, it is nearly impossible for anyone to understand what he is trying to communicate to us. You could always tell he wanted to communicate, but we often had to guess what he was trying to let us know. We would learn what would make him frustrated or upset, but as far as expressing an ailment or health concern, it could take a while to figure out.

A lot of tears were shed — from all sides. My parents and I really wanted to have my brother around. After all, James is a part of our family, and when a family is torn apart, every family member’s life is affected. It’s physically and emotionally difficult for everyone, including the individual in question.

There wasn’t really any other option. Our own funds were decreasing, and we were gradually losing the strength and ability to care for him.

Does that mean he has become a hopeless case? Does than mean all hope is lost? It also depends on how one defines hope. Hope is only lost when you decide all hope is lost. We are often trapped in a conformity of societal standards on the definition of hope, the definition of achievement, and the definition of success.

My parents and I have given up setting up unrealistic expectations. It does not mean my brother will never speak, but we have let go of expecting him to speak. Our goal, simply, is to make sure he is being heard.

Being able to communicate and feel like you are being heard does play a role in achieving happiness, so I still am working with his residential program to figure out what communication methods James can try out, and secure the staff required to help him navigate the devices. We are still on the very beginning stages of this process, but hopefully we will find a communication method for my brother that works.

As long as he is happy, that’s all that matters.